It’s been a grim few days in the UK - grey, wet and dark. So, seeing as I’ve been chained to my desk amidst the howling winds of Storm Darragh all week, you can imagine my delight when my friend Izzy text me to brag about her work trip to Naples.

However, on opening my phone my profound jealousy transformed to joy as I discovered that rather than show off her photos of the Galleria Borbonica, Izzy wanted to talk about one thing: the cult of San Diego Armando Maradona.

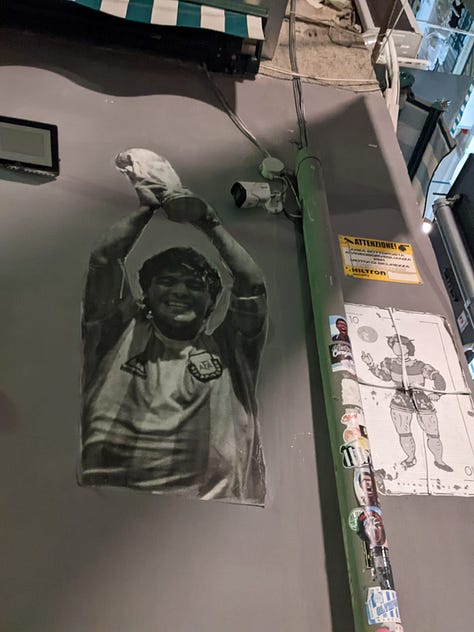

Though Izzy isn’t a football fan, the constant presence of Diego Maradona was unavoidable in Naples. His likeness is everywhere in the city, saturating the narrow streets in the form of murals, paintings, posters, statues and shrines.

As such, Izzy spent much of her down time in the city walking around the streets of the Centro Storico and Quartieri Spagnoli diligently taking photographs of the rich array of public art dedicated to Maradona (see a selection of Izzy’s photographs below).

Her question was simple: how has Diego Maradona become such an exalted figure in Naples? My answer was equally simple: it’s all about heritage.

To understand the unique place that Diego Maradona holds in Neapolitan culture, it’s crucial to understand two fundamental facts about the local heritage landscape.

First, Naples is a deeply religious and spiritual city.

Though Naples is vibrant, beautiful and renowned for its unparalleled food, it is also chaotic, crime ridden and desperately poor. In the shadow of Vesuvius, Neapolitans battle high-unemployment, poverty and the ongoing influence and legacy of the Camorra (the local mafia).

Against this bleak backdrop, many locals – organised into vibrant, close-knit communities – have developed a deep religiosity. As described by Ed Vulliamy in the Guardian, Naples is…

“the world’s last pagan city…[where] family shrines adorn corners and courtyards…people wear the cornicello for protection and to assist with fertility or virility… and Catholicism can be richly occult.”

Naples has a particularly obsessive cult of saintly worship, and the city’s saints play a central role in Neapolitan cultural tradition.

Though the most famous by far is San Gennaro – patron saint of the city and Naples’ original Christian martyr – Naples enjoys the protection of over 50 saints, each with their own unique story and powers. In turn, the centrality of saints to Neapolitan spirituality has birthed a unique tradition of religious art, meaning the city is filled with colourful graffiti, religious relics, tiles and murals paying homage to the city’s various icons.

Second, perhaps more than any other European city, Naples is obsessed with football.

The Neapolitans are renowned as a deeply passionate people. As Europe’s largest one club city those passions are channeled by the entire population into supporting one club – SSC Napoli.

Despite the club’s potted history and historic underachievement, local support has been unwavering. In the 2004/2005 season, after the club had been relegated to the third tier of Italian football following bankruptcy, Napoli could still boast crowds of over 50,000.

Much of the passion that locals have for the club is rooted in a specifically Neapolitan siege mentality. A feeling still pervades that Naples received the raw end of the deal with Italian unification. After being drawn into the Italian nation in the nineteenth century, Naples surrendered its historic riches and influence as the powerhouse cities of the north – Milan and Turin – flourished. This generates a feeling in Naples that the industrial, aristocratic north holds the city in contempt.

This sense of victimisation has been made particularly tangible through football. Not only have Napoli been historically outgunned on the pitch by northern giants Juventus, Inter and AC Milan, but Napoli supporters are consistently subjected to abusive chanting by fans from the North:

Here come the Neapolitans / Oh, what a stench!

Even the dogs are running away/ Terremotati, Colerati (earthquaked, cholera-ridden).

All of this serves to breed a sense of persecution that is not only seminal in the Neapolitan mentality, but considerably heightens the passion locals have for their football team. A victory for Napoli is understood as a victory for Naples against northern oppression and celebrated by the entire city.

This means local Neapolitan civic identity and the football team are completely fused together in a way that is totally unique. A deep and abiding love for Napoli is entwined within the fabric of the city.

These then are the two unique pillars of Neapolitan heritage on which the cult of San Diego is predicated. On the one hand, a deep civic religiosity defined by a unique culture of saintly worship. On the other, the central role of football and the local football club in sustaining a sense of Neapolitan identity.

When Diego Armando Maradona arrived in Naples in 1984, it was the beginning of one of the greatest sporting stories in football history.

There is no doubt that in the years Maradona graced the pitch at the Stadio San Paolo, he was the best footballer in the world. Whilst Maradona’s wizardry was leading Argentina to their great World Cup triumph at Mexico 1986, he was a Napoli player. Napoli-era Maradona is perhaps the greatest any footballer has ever been.

However, the adulation that Maradona receives in Naples is less about his legacy as one of the world’s most legendary players, and more about the transformative impact he had in Naples.

At a time when Serie A was the greatest league in the world, Maradona inspired Napoli to unprecedented success. That included two league title wins, a Coppa Italia, a Supercoppa Italia and European glory in the UEFA Cup. Maradona’s genius had transformed Napoli from a middling club into one of the world’s iconic sides.

The importance of these sporting victories in the Neapolitan psyche cannot be understated. Napoli’s first ever Serie A win in 1987 not only made them the first team from the south of Italy to win the Scudetto, but represented a scintillating testimony to the vibrancy of Neapolitan culture in spite of their victimisation by the those in the north. In the wake of the victory, fans placed a banner outside the city’s largest cemetery adorned with the message: “you don’t know what you missed”.

This was a generational moment in the city’s history.

But the story of Diego Maradona in Naples has always been more than a sporting success. This is a deep, abiding, even spiritual love story between a player, a club and a city with such power that is has developed a pseudo-religious quality in modern times.

The basis for this love story is a huge degree of mutual empathy, between player and city.

Maradona was born into acute poverty in the Villa Fiorito neighbourhood of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Throughout his career he actively chose to play for clubs such as Boca Juniors and Barcelona who represented poor or oppressed communities. Whilst in Spain, he was the victim of deep prejudice as a “Sudaca” – or a dark-skinned South American.

In this sense, Maradona’s experience and character mirrored that of the city of Naples. In Maradona, Neapolitans found an icon in whom they could see themselves. In Naples, Maradona found a city and a people cut from the same cloth. Downtrodden but passionate, dysfunctional but vibrant.

On his first day as a Napoli player, Maradona declared: “I want to become the idol of the poor children of Naples because they are like I was when I lived in Buenos Aires”.

That is exactly what he has become.

Maradona is everywhere in contemporary Naples.

His likeness is in bar windows, bumper stickers, advertisements and splashed onto crumbling walls as giant murals. An underground museum displays the belongings acquired by his maid's son when Maradona left the in 1991.

Diego Maradona passed away in November 2020. Though he was laid to rest in his native Argentina, the global focus of mourning was on Naples. Naples was overwhelmed with football supporters from around the world, who placed flowers, footballs, SSC Napoli jerseys, photographs, necklaces and other memorabilia in front of Maradona mural in the Spanish quarter.

This was more than a city mourning a passing sporting legend. This was worship. This was pilgrimage.

Perhaps nothing is more illustrative of the unique place Maradona holds in Naples than Bar Nilo – a tiny café in the heart of the city.

Next to the door of the bar, there is a shrine to the great Argentinian, with a strand of Maradona’s hair spinning slowly on a pedestal at the centre, as though a religious relic In the honoured tradition of the great Neapolitan saints, Maradona has even bequeathed his own religious relic to the city.

To understand Maradona’s unique place in Neapolitan heritage then, one must understand Maradona as more than a sporting figure.

Through his on-pitch genius, his off-pitch relatability and ability to provide Naples with iconic moments of civic celebration, Maradona has transcended the sporting realm. Instead, he has become revered as an extension of the city’s religious tradition.

Hold Saint Gennaro, this is a city defined by its worship of San Diego.